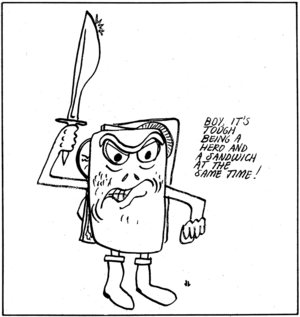

Source:The Hero, the Sword, and the Apple

| This page is a verbatim reproduction of original source material and should not be edited except for maintenance. | |

| Description |

"The Hero, the Sword, and the Apple", an article about computerized fantasy role-playing games written by Donald Brown and published in the Fall 1981 issue of Apple Orchard magazine (pages 23 to 25). |

|---|---|

| Source | |

| Date |

Fall 1981 |

| Author |

Donald Brown / Apple Orchard |

| License |

It is believed that the use of this copyrighted item in Eamon Wiki qualifies as fair use under the copyright law of the United States. |

| Other versions | |

A new type of game has swept the world's computers. No longer are gamers sweeping away foolish Klingons (or Klarnons or Klopklops). No more little bricks are being knocked out. No invaders are being wiped out with beeps and buzzes. Instead, the gamers are wandering through underground tunnels and old houses, trying to defeat the puzzles and monsters that abound.

These new games are called "role-playing" games, although that isn't quite accurate because almost all computer games put you in a different role. (You don't really clear asteroid fields for a living, do you?) The difference is that these games have you directing the action of an individual, not the ship or whatever vehicle around him/her. These games are the foster child (I might use another parental description, but not in a family magazine!) of a non-computerized game called Dungeons and Dragons.

So this article will try to shed some light on these games – how they came to be, what's there now, and what they might become. I'll be mentioning a new game called SwordThrust, which in my unbiased opinion is the absolute best Computerized Fantasy Role Playing (CFRP) game available today. (Mr. Brown's opinion of SwordThrust is understandable, inasmuch as he wrote it. –Ed.)

The slew of CFRP games can trace their inspiration back to the first fantasy role playing game of Dungeons and Dragons by Dave Arneson and Gary Gygax. Although many other FRP games (noncomputerized) have come along, D&D is still the prototype for fantasy role-playing.

In D&D and the like, roughly six people get together to play the game. All but one of the people assume the roles of characters that exist in a weird, magical world. Numbers are randomly generated to define how strong, agile, intelligent, and attractive these characters are. The players also buy armor, weaponry, and other supplies for their characters to use.

The remaining player is called the Dungeon Master, and he represents the rest of the universe. Before the other people come, the Dungeon Master designs a tunnel complex (or a building, or whatever) that the characters will be exploring. Then, when everybody gets together, the Dungeon Master runs the game by telling the other players what their characters see, and interpreting the results of the characters' actions.

For example, the Dungeon Master might tell the party that they are in a long corridor with a door at the north end. One of the players says that his character, Sidney the elf, tries to open the door. Chuckling evilly, the Dungeon Master tells the group that the door was booby-trapped; when it was opened, a trapdoor opened in the floor, and the entire party fell in. They now find themselves facing a dragon, one flight down.

Eventually, the characters will have killed all of the monsters, and will have taken the treasure from the place (or, will have been so badly scared that they leave, vowing never to return). These characters then return to a town where they can purchase new and better gear to be used in the next set of crises to be devised by the Dungeon Master.

No two ways about it, after a hard day's work at the office there's nothing that beats relaxing by slaughtering an orc patrol. Unfortunately, not only do you need a fairly large number of people around to play the game, but you also need a person with a creative mind and a capacity for work (read "sucker") to act as Dungeon Master. Not only does Dungeon Mastering require a lot of work, but a poorly run game is worse than watching My Mother the Car reruns on the boob tube. Since the major problem in fantasy games is the quality of the Dungeon Master, there must be a better way... and for one or two people too, not only a larger group. Hmmm... maybe a computer...

Enter Woods and Crowthers, from MIT. They developed the first game of Adventure. In it, you talked to the computer, giving one- or two-word commands as it led you through the Colossal Caves. Your goal was to pick up as much treasure as possible by getting around inanimate blockades. (Some of these blockades were disguised as monsters, but they merely sat there, blocking your way. Speaking of which, how do you get past the green snake?)

Many other Adventure games have been written. Although most games use the same format as the original Adventure, some games have added graphics, trying to represent what you see on the screen. This isn't necessarily a step forward, as the computer display images are far less detailed than what the mind might conjure up unaided. Put another way, nobody can scare you as thoroughly as you can. However, the pictures on many adventures – particularly the superlative Wizard and the Princess by On-Line Systems – are quite good. Automated Simulations has tried to satisfy both sides by drawing a picture on the computer's screen, and also having descriptions in a booklet to which you can refer. Trying to look up these descriptions can be distracting, but they're there.

Probably the consistently highest quality adventures have been written by Scott Adams, but many other authors have entered the act. A few I'd personally recommend are The Wizard and the Princess by On-Line Systems, Lords of Karma by Avalon Hill, and The Prisoner by EduWare (be prepared for hours of utter frustration with this one).

What's wrong with today's crop of games? Well, starting with a minor gripe, I have grown very tired of "Guess the Word I Want". This is a sub-game which the computer plays with you; you know what you want to do, but what syntax will enable the machine to understand? The very worst case I found was in one game. I was standing in front of an open door to the north of me. I want to go through the door. I try "NORTH", "ENTER", "ENTER DOOR", "ENTER BUILDING", all with no luck. Believe it or not, it wants and will accept only "GO DOOR", which may come naturally to the Incredible Hulk, but not to us semi-normal types. The problem is confounded by the fact that there is (usually) no way to get a list of acceptable commands. Even a list of the acceptable action verbs would be a great help.

This is part of the overall problem that any computer program is not going to be as intelligent as a human running the dungeon would be. A far more serious result is that the computer program will permit the player to be no more creative than the programmer was. Example: a locked door in the dungeon. Elsewhere, a chopped-down tree. Aha. We'll get the tree and use it as a battering ram to knock down the door. But if the programmer didn't tell the computer what to do when a player tries this, the computer can only give a small "I DON'T UNDERSTAND" or "NOTHING HAPPENS" (which is patently ridiculous). Unfortunately, this problem is not likely to be solved; a good human Dungeon Master will outperform the machine. (Whew!! –Ed.)

Another major area in which most adventure games fall short in comparison to fantasy role-playing games is in combat. Most Adventure games simply do not have satisfying combat rules. Combat is either predetermined (if you attack the first beastie you kill it, if you attack the second beastie it kills you, etc.); or governed by one random number regardless of conditions (you will kill the dwarf 50 percent of the time, the dwarf will kill you 25 percent of the time, etc.). The non-computerized games have a much richer combat system, with your chance of hitting (and how much damage you do) based on a variety of factors such as your dexterity, the weapon you use, and your experience.

For the dedicated game-player, the greatest shortcoming of the computer games has been the survival and growth of characters after each episode. The non-computerized D&D process involves such growth in wealth and skills for the characters. The party leaving a dungeon has new knowledge that will help them in the future, they have gold to buy more supplies, and possibly a powerful new weapon or two. In many computer games, once your character has killed the vile beastie, has stripped the rooms of all their treasure, or has escaped from the island alive, that's it. You could play another game, or even play that game again (if there is enough randomness to make it interesting), but all that effort you put into the dungeon and all of the wealth you took out is irrelevant.

This concept of character growth was important to me in writing SwordThrust. The first or master diskette has programs that control the creation and equipping of your new characters, and there is a cavern provided as a scene for their exploration and looting activity. Further adventures are and will be on separate diskettes, but the characters' personal histories and accumulations will be stored. I have also tried to make the combat situations more realistic. The type of weapon you choose has a great effect on how effective you'll be with it; and the longer you use a weapon, the better you'll become with of it.

The "richness" of a game is proportional to the amount of detail and the number of alternative courses and effects. These in turn are limited by the computer's available memory and the disk's capacity for storing data. HiRes displays in particular are large memory consumers. The two-disk system is one solution to the problem of memory capacity. And with hard disk storage using the contents of many diskettes on line... oh boy!

What's to come in CFRP games? In a word, more. In addition to new, exciting, and even more clever text adventures, HiRes graphics adventures are possible. Even animation. Competitive games between two players are in the planning stage. This could even be two or more players with separate computers, connected by 'phone line and Modem. How about games using speech synthesizers and speech recognizers? Games using bio-feedback units? As with magic, with computers, all things are possible.

But lo! Hear the muttering of monsters from your RAM chips! See the shine of gold glowing from your keyboard! Smell the mildewed walls rising from your disk drive! The dungeons are waiting. Put aside your word processor, your CalcCalc program, your checkbook... and come!

Donald Brown is a recent graduate of Drake University. He became involved in microcomputing when his father bought an Apple II with a serial number of 124. Many popular programs by him can be found in various computer clubs' program libraries, including Automatic Menu, Star Wars Adventure, Fizzbin, and The Wonderful World of Eamon. He is currently working for CE Software, a new software firm from Des Moines, IA.